Joe Goldberg was born in 1947 in Seattle, and was raised near Spokane in Eastern Washington. He was educated at the University of Washington until he dropped out in 1968 at the encouragement of some of his teachers who knew that academic rigor wasn’t going to teach (or tame) this most natural of artists.

Joe Goldberg was born in 1947 in Seattle, and was raised near Spokane in Eastern Washington. He was educated at the University of Washington until he dropped out in 1968 at the encouragement of some of his teachers who knew that academic rigor wasn’t going to teach (or tame) this most natural of artists.

OWL AT DUSK, 2005

His first few exhibitions in the late 1960s, with Francine Seders Gallery in Seattle, revealed two separate inquiries into abstraction. At the time he was living as a caretaker in a studio that was part of the gallery and then later in the basement of Seders’ Greenwood area gallery. He was producing small landscape drawings and paintings that were somewhat surrealistic in nature. At the same time he was beginning the course of abstraction that would define his early career. In these first delicate works on paper, small shapes of colors floated within larger planes of color, the central shape often echoing the shapes the larger field. They were mindful of both the Russian Suprematist work of Kasimir Malevich and the work of post-war abstract artists such as Albers, Rothko and Held. This paring down of essentials had, by the 1970s, become a direction followed by various artists across the United States. One thinks of California’s Robert Irwin or John McCracken as easily as New York’s Brice Marden or Kenneth Noland.

FACET, 2007

By 1975, these works on paper would develop into larger works in oil or wax over linen stretched over wood panels. The central floating images became striated and sometimes even gestural. A series of tall vertical paintings in the late 1970s and early 1980s suggested classical columns or stacks of rectangles within the larger rectangle.

FACET, 2007

By 1975, these works on paper would develop into larger works in oil or wax over linen stretched over wood panels. The central floating images became striated and sometimes even gestural. A series of tall vertical paintings in the late 1970s and early 1980s suggested classical columns or stacks of rectangles within the larger rectangle.

Goldberg had traveled in England in 1978, staying for a month in an Elizabethan country home near Sussex, visiting ancient Roman ruins and Greek revival manors. He would later travel extensively in the western regions of the U.S., particularly the Southwest where the artist visited Zuni and Navajo reservations, Anasazi ruins and Hopi pueblos.

In 1980, Matthew Kangas said of Goldberg, “His true significance…lies in the fact that he turned his back on “mysticism” in art and squarely faced the more rewarding challenges of 20th century painting (cubism, neo-plasticism, abstract expressionism, color field painting), as routes to personal expression.”

By the early 1980s, Goldberg had perfected the technique of encaustic painting for which he would become most well known. By mixing brilliantly hued raw pigments with translucent beeswax, Goldberg is working with a tradition of painting with wax that dates back to Greco-Romans working in Egypt in the third century. Goldberg builds his painted surface with layer after layer of color until a palpable luminescence is achieved. The surface is flamed and buffed developing a waxy, lustrous sheen.

In his 1981 show with Foster/White Gallery, Goldberg debuted a suite of irregularly shaped paintings in encaustic on linen over wood panels. Generally still somewhat geometric in nature, they floated like unfurled banners or waving flags against the wall. In most of these a vaguely rhomboid panel of shimmering gray would contain an interior shape just as solid walls frame a roomful of space. He would revisit these shaped canvases in his 2015 exhibition with Greg Kucera Gallery. OPEN SKY, 2007

One of his most innovative shows was of true three dimensional paintings; again of landscapes but this time somewhat more urban. The remnants of architecture appear as buildings that protrude from the wall. A corner view might be held in perspective or a courtyard would be suggested by three walls.

OPEN SKY, 2007

One of his most innovative shows was of true three dimensional paintings; again of landscapes but this time somewhat more urban. The remnants of architecture appear as buildings that protrude from the wall. A corner view might be held in perspective or a courtyard would be suggested by three walls.

In the mid-1980s Goldberg produced paintings that were oval shaped or had round or oval shapes in them suggestive of planets or their rings and moons. In the later 1980s and early 1990s a broader sense of abstraction encompassed the suggestions of trees, rural architecture, even pueblo ruins the artist had seen in the southwest.

As the work progressed through the 1990s, this expansive vision of the natural world embraced an increasingly larger scope of imagery though often reduced to its essence by a rigorously applied sensibility of abstraction.

In the late 1990s, Goldberg exhibited a group of landscapes depicting the familiar forms such as gorges, ridges, fields as well as Soap Lake in Eastern Washington, where the artist had been living since 1984. These land, sky and waterscapes revealed that this appreciation of the natural world has been the most enduring images in Goldberg’s work. In more recent paintings, Goldberg adds elements of weather and observations of the sky to these abstracted landscapes. Lightning, to be more specific, was a recurring theme in a number of works. Other paintings are overtly representational with figurative elements in the forms of silhouettes and skeletons, as well as group of haunting paintings of owls in flight.

OPEN SKY, 2014

The paintings since 2000 have often returned to the severity of the earliest work, though now filtered through the artist’s keen sense of art historical precedence and of the grandness of nature surrounding him, often filtered through Goldberg’s earlier interests in Minimalist painting. Several pieces investigate a severely reduced composition—a field of rich, nuanced white is edged with small bands and rectangles of high key color intruding slightly into it. These are mindful of the late Mondrian works and also of Motherwell’s ongoing Open Series in which he would create a painted space suggestive of the openness of doors or windows without being representational. Similarly, much of Goldberg’s past and present work seems related to architecture. Suggestions of archeological relics, mosaic panels, floor plans, doors, tunnels, arches, windows and columns, have figured in nearly every body of work.  DARK OF NIGHT, 2009

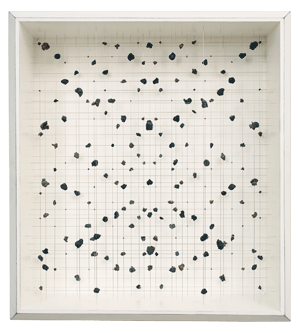

In addition to the encaustic paintings, Goldberg created mysterious 3-dimensional box sculptures. Minimal wooden boxes contained gridded compositions made of tightly strung wires with coke cinders attached and arranged in seemingly random compositions that resemble constellations of stars or rocks strewn across a desert landscape. When viewed from exactly in front of the sculptures, the viewer realizes the coke cinders are arranged in strictly symmetrical patterns.

DARK OF NIGHT, 2009

In addition to the encaustic paintings, Goldberg created mysterious 3-dimensional box sculptures. Minimal wooden boxes contained gridded compositions made of tightly strung wires with coke cinders attached and arranged in seemingly random compositions that resemble constellations of stars or rocks strewn across a desert landscape. When viewed from exactly in front of the sculptures, the viewer realizes the coke cinders are arranged in strictly symmetrical patterns.  I noticed if you have chaos on one side and then mirror it, on the other you end up with balance, order, and a peaceful stillness. —Joseph Goldberg

I noticed if you have chaos on one side and then mirror it, on the other you end up with balance, order, and a peaceful stillness. —Joseph Goldberg

MOTH, 2011

The Northwest region has so little history with reductive art that Goldberg seems a refreshing comment on a minimalist aesthetic with his newest works. Several pieces investigate a severely reduced composition—a field of rich, nuanced, loosely brushed white is edged with small areas of high key color intruding slightly into it. Whether painting the indigo space between the glowing stars in the deep, dark night skies of Eastern Washington, or poetic suggestions of stars reflecting in the marshy water of a pond, Goldberg has produced a sensitively wrought body of work. In the starkest paintings, Goldberg renders the expansive white ground between disparate objects of rural detritus abandoned at the edges of a snow covered field. A look at Goldberg’s entire career reveals him to be a peripatetic artist, circling back from time to time to meaningful images and painterly issues which have fascinated his constantly seeking curiosity. At the same time it shows the remarkable consistency of thought peculiar to the best of artists.

A look at Goldberg’s entire career reveals him to be a peripatetic artist, circling back from time to time to meaningful images and painterly issues which have fascinated his constantly seeking curiosity. At the same time it shows the remarkable consistency of thought peculiar to the best of artists.

Joseph Goldberg’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Northwest Art in La Connor, WA; Seattle Art Museum, WA; Tacoma Art Museum, WA; Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; Bellevue Art Museum, Bellevue, WA; Museum of Arts and Culture, Spokane, WA; Nona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France; Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, BC; and San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA.

THAW, 2010

His work is in the permanent collections of Brooklyn Museum of Fine Art, NY; Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; Seattle Art Museum; Whatcom Museum of History and Art, Bellingham, WA; Wichita Art Museum, KS; Long Beach Museum of Art, CA; and Municipal Museum of Dublin, Ireland; and Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Victoria, BC.