|

|

The following article is taken from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 23, 2004:

Hammond's Work is an Acquired Taste - Try It and You Just Might Like It By Regina Hackett

Playing dead works for Jane Hammond. She encases her figures in crustations of color, freezing them to add a final layer of fun-house illusion to the carnival world she coils inside the contemporary grain.

The trick is, the final layer's the truth. All paintings are stills. Hammond force-feeds her paintings with image glut and then insists on a dead-calm surface. It's a move nobody else is making, maybe for a good reason, and yet Hammond pulls it off with her own panache.

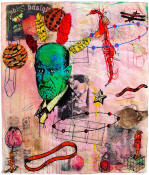

Take "Freud With Feathers" (above) paint, collage and mixed media on paper, 44 inches high by 39 inches wide. In a photo reproduced in the lower left corner, a girl in a leopard skin is sharing the coat with the cat, carrying the animal across her shoulders, a situation that looks both cozy and dangerous.

Nearly lost in pink mist is a clown nursing a pig. Pick a card, any card. She's got ropes, snakes and river boats; puzzles, dice and the down-and-out. All these are the ground sliding around under the painted figure of Freud, who's green like a toad and wearing feathers.

People tend to read Hammond's paintings, and now she's painting in book form. Other paintings are shaped like matchbooks, with silver bars impersonating the staples.

You get the feeling that if you turn your back, cats will roar, girls wiggle and monster men leer and grin. She's an acquired taste, but if you give her a chance, she'll grow on you.

© Copyright The Seattle Post-Intelligencer

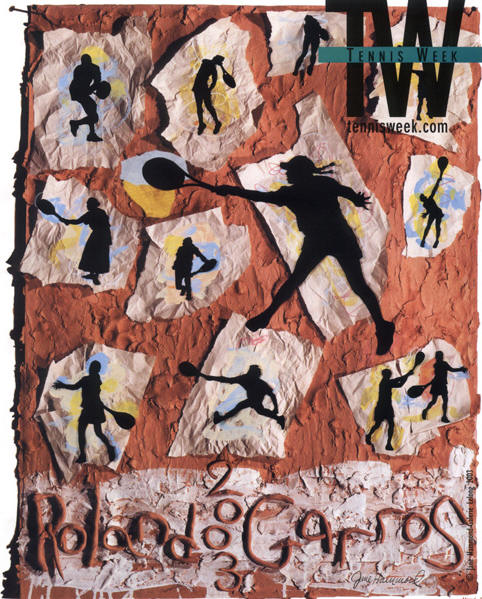

Article from Tennis Week magazine, May 2003:

Tennis Week Tennis Week

The following article is taken from the New York Times, October 13, 2002:

To a Painter, Words Are Worth a Thousand Pictures By Amei Wallach

In the beginning for the artist Jane Hammond is the word. It's impossible to talk about her painting without resorting to literature (not to mention Santa Claus, molecular biology, phrenology, Mao Zedong and the American flag). She'll pillage anything from her eclectic library or her notebooks of names, from those of pets to those of English castles.

The best metaphor for the method behind her rollicking, erudite, street-smart, angst-ridden, encyclopedic paintings is writing. To make the point, Ms. Hammond passes along an article, "New Wave of Writers Reinvents Literature," by Michiko Kakutani, the senior book critic at The New York Times. The writers mentioned range from Salman Rushdie to the young Dave Eggers and Zadie Smith. In Ms. Kakutani's words, they write "Big Tent Novels: huge, inclusive, often mythic works that attempt to capture the chaos and cacophony of the world through whatever means come to hand."

Substitute the word "painting" for "novel," and you've got a fair description of what Ms. Hammond is up to. And that is to make paintings "as complicated, inconsistent, varied, multifaceted as you are, as I am, as life is," she said. She spoke on a recent afternoon in her sun-splashed studio-loft in SoHo, where she lives with Craig McNeer, a homemaker, amid works in progress and wildly blooming potted plants.

"I think my work deals very directly with the time that we live in," Ms. Hammond said. "There's a surfeit of information, increasingly bodiless because of the computer, and I bring to this an interest in how meaning is constructed."

For example, she will paint props — masks of Einstein and King Tut, puppet parts and a trompe l'oeil Arc de Triomphe — and pin them to the wings of a painted double stage on which a bear prances and a geisha dances (the geisha's head a likeness of Ms. Hammond). All these and more fill the 12-by-21-foot canvas of "Back Stage, Secrets of Scene Painting" (shown last spring at the Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris), while ropes, pulleys and backstage ephemera seem to jut out into the viewer's face. The painting is as much tour de force performance as a meditation on the nature of performance and manipulation.

"My work is about, `O.K., I grew up in a world of mediated imagery,' " said Ms. Hammond, who is 52 and has sold out every show since her first one in 1989. "How am I going to be an imaginative, spirited, authentic, private, living, breathing self? How do I shape this stuff?"

She will go as far as devising literary strategies to achieve her time-bending, media-blending mind teasers. One example, her nine-year collaboration with the poet John Ashbery, is the focus of a traveling show, organized by the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art and currently at Blaffer Gallery at the University of Houston. Mr. Ashbery's part, he writes in the catalog, lasted about four minutes in 1993, when in response to a request from Ms. Hammond, he "made a tour of a walled-off room somewhere in my unconscious" and returned with titles for paintings. She wanted titles to suggest paintings instead of the other way around. Ms. Hammond was hardly expecting 44 titles to emerge from her fax machine. She certainly didn't predict that Ashbery phrases like "A Parliament of Refrigerator Magnets," "Do Husbands Matter?" and "The Wonderfulness of Downtown" would inspire a raucous flowering of 62 paintings.

Last summer, Ms. Hammond completed the last of the Ashbery-titled paintings, "Prevents Furring," after looking up "furring" in the dictionary. "Each meaning was more recondite and weird than the other," she said, "but one meaning is a coating of the tongue. So it clicked in my mind that when you read about old medicine or herbal medicine today, there are all these claims for cures that are romantic and fabulous." She invented "marrow tea," a product with a list of improbably miraculous benefits that she presented as a painting shaped like a collapsed box.

And that was the end of a nine-year project for an artist who said she had to have "something to do, otherwise, total panic." To avert crisis, Ms. Hammond had already begun working in new directions. One result, the artist book "Be Zany, Poised Harpists/Be Blue, Little Sparrows," is on view at Dieu Donné in SoHo. It, too, is a collaboration with a poet, Raphael Rubinstein.

A decade ago, Ms. Hammond heard Mr. Rubinstein reading his poem "Six Sex," a bawdy tour of European cities in six stanzas, each with six lines of six words of six letters. The poetic form is called oulipo. "There's a formal strength," Ms. Hammond said. "It's not anti-self-expression, but it's not just self-expression. It's driven from the outside in, and the inside out." For the artist book, she also chose Rubinstein poems based on two stanzas and four stanzas, then commissioned one of eight. She illuminated each poem with a different system of image-making, from digital renderings of vintage postcards backed with erotic drawings to pull-out photographs and a fold-out print. For each book in the edition, she also concocted different covers from collaged and handmade paper.

Both the stringent poetic form and its infinite possibilities tally well with Ms. Hammond's own predilection for systems. For decades it has been her practice to limit all her paintings to mix-and-match selections from a total of 276 found images.

Multiplicity is her goal at all costs. Ms. Hammond has an abhorrence of the signature style. She wants her exhibitions to look like group shows. For all their inventiveness, however, they don't. She can escape the rectangular canvas; she can't escape her sensibility. But she can riff on it, sometimes revealing herself, more often concealing it.

A post-Ashbery painting like "Dizzy Dice" (2002) recapitulates her images in black and white as faux three-dimensional matchbook covers, an aloof commentary on objects of advertising and desire. In "Good Night Nurse" (2000-1), Mr. Ashbery's twist on the title of the children's book "Goodnight Moon," Ms. Hammond's impulse is autobiographical.

"Good Night Nurse" is set in a red studio, recalling "The Red Studio" of Matisse. The space, however, is eerie and deep, as in a set for a play. Young boys play leapfrog at center stage, a catcher's glove, soccer ball and other boy stuff at their feet. Their actions are frozen in white, like the marble of memorials. Scattered about are sarcophagi and the disembodied head of a nurse. Like many of her paintings, "Good Night Nurse" first appeared to her in a dream. It occurred after she had visited her nephew, now 13, who for years has been struggling with a life-threatening disease. She dreamed he had died, and she was letting him choose the shape of his coffin.

Now she is working on paintings shaped like gigantic three-dimensional open books. The pages of these books are studded with rebuses. One spells "Ursula Andress"; another, on the facing page, spells "Paul Revere," an unlikely pairing of cultural icons. "With the Ashbery collaboration, I went from words to pictures," Ms. Hammond said. "Now I'm going from pictures to words." She has begun yet another collaboration, for a benefit sale for Dieu Donné. This time her collaborator is a psychic.

© Copyright The New York Times Company

The following article is taken from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 10, 2000:

Painter Jane Hammond Creates and Breaks Her Own Rules by Regina Hackett

In 1988, Jane Hammond assembled a box of 276 images taken from can labels, wrapping paper, comics, puzzle pieces, film stills, medical and botanical drawings, illustrations from mysteries, magic-trick manuals, children's books and early-20th-century advertisements.

They've served as her working tools ever since, numbered props used in carnival encounters that often occur with idealized portraits of herself, a blanked-out model's version of the lively original. This "she" of Hammond's projection is a kind of ventriloquist's dummy through which Hammond can insert herself into the world of her painting. Her face shows up on Esther Williams' body, for instance, as she climbs with showboat grace out of a pool.

Hammond, whose work is on view at the Greg Kucera Gallery, admits she is a "more is more" kind of person, and this affects not only her imagery but the materials used to generate it. They include rubber stamps, color-copy transfers, linoleum block prints and various paints, pencils, inks and solvents applied to rice papers as well as canvas. Once the painted and collaged imagery starts to achieve visual coherence, she might paint around and over them in acrylic and gouache or sometimes oil until a ragged tale emerges.

Her painted atmospheres serve as animating forces. From them, her forms derive the confidence to bloom in the congested yet fluid ground of their planting.

Like Jonathan Borofsky and Kiki Smith, Hammond is a conceptual surrealist, meaning she likes the play of ideas not dependent on logic for their sense but requires the images that grow from them to follow a carefully codified set of behaviors.

Like many professional gamblers, she uses a system to pick winners, in her case, the paintings that survive to leave the studio. She frequently changes the system or uses it only once. She has limited herself to certain colors or used the map of a fly's flight path as the entry point for a body of work. For as long as she was interested in where the fly led her, buzzing confusion was her byword.

No system, however, is allowed to overrule her intuition. She wants to create what Paul Valery once called the "sensation of a story without the boredom of its conveyance." Because the meaning in her work is meant to be open-ended, she didn't use titles until 1993, when poet John Ashbery responded to her request and provided her with a list of 44 ready-made ones.

To date, she has used all but eight, some five or six times each. "The Soapstone Factory" and "Pumpkin Soup" have proved favorites, while "Prevents Furring" has so far left her cold. She wants the paintings to emerge from the title, instead of the usual process, of the title emerging from the painting.

To this end, she lets the title rattle around in her head until a likely image pops up. That's her original idea, which she modifies within the context of whatever part of her 276-piece image library seems relevant or by whatever rules present themselves as necessary prods to the creative process.

"Part Time in the Library" (oil on canvas, 74 inches high by 98 inches wide, 2000) features an arched, architectural interior as a stage set. In this library, reading is theater. The action derives from characters who are ordinarily confined within the context of historical narrative paintings and/or novels but find themselves free (or freshly burdened) for the first time.

A graceful woman dressed like a 19th-century European peasant stands on a giant glass snow scene, carrying a model of New York's Guggenheim Museum on her head. Because she might easily come from a painting in the museum's collection, Hammond is suggesting a reversal of the natural order: the container exchanging places with the thing contained.

Everything else in the painting is some sort of play on this theme. Hot philosophy needs a cool base, and Hammond provides with the gunmetal gray architectural setting. Against it, flush color can weaken or become feverish, complicating the drama but adding greatly to its allure.

Hammond says the act of painting is a "cross between high philosophy and cement work." Some paintings take her months or more and yet look fresh and labor-free, as if she snapped her fingers and made them appear. What's left after labor's long hours is nothing less than new life.

|