|

|

Joseph Goldberg

Review by Matthew Kangas

March 15, 2015

See more at: Visual Art Source

Regina Hackett reviews Joseph Goldberg

Regina Hackett reviews Joseph Goldberg

Joseph Goldberg's new encaustic paintings glow with a mute radiance

Link to review online: here

By Sheila Farr, Seattle Times art critic

Entertainment & the Arts: Friday, March 11, 2005

Joseph Goldberg has come roaring back with a debut exhibit at Greg Kucera Gallery that re-establishes him as one of the region's most charismatic painters.

The new work has the resolve of the early paintings that made Goldberg a hot property when he first showed his mouth-watering encaustics in the 1970s. Since that time, Goldberg's painting has at times sparkled, at times seemed stuck, and occasionally struck out in directions that rocked his reputation. Now he's assembled a sizable show that fills the gallery with imagery that's rich and varied, while only improving on the delicious surfaces that have long been his forte.

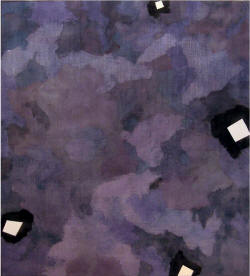

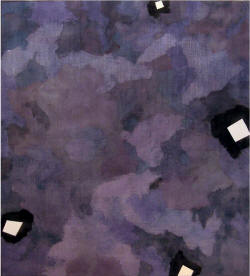

Those who love the old Joe will have plenty to be happy about: His suave desert abstractions and fields of warm gray still sprout minimalist bands or patches. Color vents through the burnished surface like magma bubbling under a glaze of ash. The more daring paintings, such as "Constellation I" look skyward rather than across the abstracted landscape, into all-over patterns that suggest midnight accumulations of cloud in a spectrum of blues and grays - views through 1,000 miles of space. Stars appear as diamond shapes of flat white nested in black shadow. The ramped-up contrast is risky, but effective.

Such innovations make the new paintings exciting, pushing past the easy elegance that at times made Goldberg a decorator's darling of tasteful restraint. Now he's willing to dive head-on into luscious color and proves it with "Yellow Dawn" a radiant stack of horizontal bands simmering in pink - one of the most joyful images in Goldberg's oeuvre.

A Seattle native who grew up in Spokane and attended the University of Washington, Goldberg, 57, started his career in Seattle. He hit pay dirt in the 1970s, when he defined his style by working with encaustic, a mixture of heated wax and pigment that few local artists were using at that time. Since then he has become a consummate practitioner of the technique. He rode-out the faddish popularity of wax as an art material, which came and went in the 1990s, to remain the region's master of the medium. The glowing skin-smooth surfaces he creates can make you swoon.

Exhibit review

But ravishing surfaces alone do not an artist make, and with Goldberg the biggest question mark has always been how he would progress beyond the spare images that brought him a rush of early popularity. The little floating triangles of the 1970s referenced patterns of tribal art and the pared down geometry of later paintings drew from the landscape and shapes of pueblo architecture. This show features a section of Goldberg's more representational images, which still upset those fans hooked on the abstractions. While I was viewing the show, a gallery visitor complained to Kucera that only Goldberg's abstracts were good.

I disagree. Goldberg is generating heat in the studio again. His landscape "Sage" pays tribute to the late Northwest painter Jay Steensma with its lonely outcrop of buildings and depressive barren countryside. Goldberg even manages to bend his sleek technique to resemble the slapdash watery paint that Steensma flung down. The searing-eyed "Hunter," a flying owl that startles out of thin air, speaks of Goldberg's geographical location as well as his place in Northwest art history. While alluding to Morris Graves' famous bird metaphors, "Hunter" doesn't in any way mimic them. I like Goldberg's strange skeleton paintings, too, the chalky calcium smears over a surface like rusted metal: everything in the process of decay.

The grand finale - and the big surprise - is the small selection of paintings in the back gallery. Here Goldberg rethinks the stylistic breakthroughs of earlier abstractionists Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich in paintings such as "Yellow Black."

Goldberg rekindles that pioneering minimalism, placing slim bands of color against the edges of a white ground. Yet beneath the broad expanses of white - unusual for Goldberg - teem layers and layers of smoldering color.

Sheila Farr: sfarr@seattletimes.com

By REGINA HACKETT, SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER ART CRITIC

Friday, March 11, 2005

The hard transparency of Joseph Goldberg's painting is no small thing.

For three decades, he has been blow-torching his way into his version of a landscape. It is peopled with ghosts, bones and architectural ruins; the colored light of flowers in a desert, long horizon lines, blunt trees and burnished bodies of water.

Then there are his skies at night. His blues climb all over each other, and his vehement stars eat holes the dark.

Goldberg is an encaustic painter. He binds beeswax to linen by means of industrial heat and presses powdered pigments into the still-warm surfaces, using a palette knife, a brush and sometimes his fingers.

Born in Seattle in 1947, Goldberg grew up in Spokane and spent his 20s and most of his 30s in Seattle before heading back to the desert in the eastern part of the state, tired, he said, of the city's endlessly wet gray. Born in Seattle in 1947, Goldberg grew up in Spokane and spent his 20s and most of his 30s in Seattle before heading back to the desert in the eastern part of the state, tired, he said, of the city's endlessly wet gray.

Thousands of years old, hot-wax paintings were rare in contemporary art when he started experimenting in the 1970s.

Besides Brice Marden and Jasper Johns, Goldberg had the medium almost to himself.

It's common now, not that Goldberg knows who's using it. His memory is saturated with vast amounts about art history, especially ancient art history, and he connects to the modern period beginning with Kazimir Malevich, but since leaving Seattle he hasn't paid much attention to the current scene.

Not that he wouldn't want to. "I'd like to see what problems other painters give themselves, and how they solve them," he said at the Greg Kucera Gallery on Saturday, looking startled that so many people showed up to hear him speak.

"It's odd," he said in an aside, "considering that I have nothing to say."

Not true, although it's true he is used to silence, the silence of the desert, the creak of his house in a high wind, the engaged play of himself in the studio, trying to render a fragment of what he has observed in nature.

The paintings in the first gallery are the most abstract, and their surfaces are thinner than usual, giving the linen grounds a silky look.

The bones in "Sand Lights" (55 inches high by 48 inches wide) are white fists pulled violently apart into horizon lines stacked six high and becoming increasingly fragmentary as they descend the canvas space.

Stare at a thing long enough, it starts to waver. Goldberg paints the uncertainty of seeing, not the moment of connection between landscape and  viewer but the moment after, when the eye no longer can frame its experience. viewer but the moment after, when the eye no longer can frame its experience.

In "Constellation 1" and "Constellation 2," (both 52 inches high by 48 inches wide), blues that have started to crumble fold into each other, and stars, blank whites, peer out from black holes. The painter is pressing the extremes of contrast in what he realizes is a meager effort to imitate the effortless contrasts he sees daily in the desert.

In the second gallery, the land comes more clearly into focus. "Middle Thompson" (24 inches high by 34 inches wide) could be the indistinct negative of an overexposed photo achieving an improbable form of glory. Bare tree trunks are whitening verticals that look dead but sustain smeary green branches of blackened life. Ash is settling over this scene, and the lake is made of ice.

Goldberg spends most winters snowed in. The paintings in the third gallery are blanketed spaces, whites pushing everything else to the edge, where a sliver of yellow may be what's left of a tractor and a black wedge a glimpse of a barn.

With small glints of buried color, his activated empty spaces hold the ground in a cold embrace.

A few of these paintings could be tributes. Jay Steensma's elastic space informs "Sage" (24 inches high by 30 inches wide), and those are Steensma's shadow figures in "Sky Over Taos" (30 inches high by 36 inches wide). Several of the skeleton paintings evoke George Chacona's skeleton paintings, force merged with grace.

Some say the world will end in fire. Goldberg uses the fire of a propane torch to make a case for an ending in ice. After long silences and a few hit-or-miss exhibits elsewhere, he is still one of the best painters this region ever produced.

Whether experimenting with abstract expressionism, cubism or color-field painting, Seattle-born encaustic painter Joseph Goldberg has a knack for extracting the simple, gritty essence of his subjects. Goldberg's landscape paintings of the high deserts of eastern Washington, for example, capture this environment's inherent abstract beauty, while his gray color fields, punctuated by thin strips of yellow and black, suggest foggy city streets. All in all, Goldberg is a favorite of ours and his new exhibit at the Kucera Gallery is a must-see. - Seattle Magazine, 2005

by Mike Rust

Review of exhibition Fresh Air C. 1930-97 at Museum of Northwest Art, 1997

Last week the newly remodeled First Street facility for LaConner's Museum of Northwest Art opened its doors, in an atmosphere that combined elements of a down-home Skagit barbecue, a school graduation, and an (urbane) northwest coast potlatch.

Local and Seattle artists drank champagne and crunched vegetables with collectors and connoisseurs from out of town, and cross-dressing farmers peered at paintings over the shoulders of ex-fishtown eco-radicals. The mood was expansive.

The new building, itself one of the stars of its own opening show, is so transformed that the work of architect Henry Klein and his design team (donated to MONA by Klein's firm) is more a redemption than a remodel. The aggressive, unrelenting commerce of La Conner in recent years had reached an apotheosis in the (former) Wilbur Building, an expensive and very ugly imposition on the town's waterfront street. However its size and location made it an ideal candidate for the museum.

The facade, which had seemed willfully brutal, has been softened by an enclosure of vertical red cedar lathe. Inside Klein created a large exhibition space on each floor and then connected them with a broad spiral stair. Above it but slightly offset, a large circular sky window allows sunlight to stream down into the building's main- floor volume. The newly unified result is clear and graceful; it also reiterates the essential and intimate relationship that northwest art continues to have with the natural world.

Curated by Barbara James the show is, despite the brochure's disclaimer, an historical anthology of northwest art. It doesn't approach exhaustiveness, of course, but does offer an opportunity to see representative pieces from some of the best artists now working. The generations born c.a. 1920s have provided recent work; particularly strong examples from among these are by Philip McCracken, Clayton James, Gaylen Hansen, and Richard Gilkey. The Tobeys, Graveses, Andersons, Tsutakawas, Iveys, Tomkinses, Horiuchis, Callahans are here (and a lovely Helmi gouache); and among the more than thirty selections from the work of these "old guys" are several so close to being masterpieces that it's unseemly to quibble. My own choice would be Morris Graves' Sea, Fish, and Constellation. Many of these works are from important private collections that are normally inaccessible. But against a background of canonical northwest works the real excitement of this show is in the work by artists who are putting themselves out there now.

Each artist was asked to write a very brief statement of aims, to be printed and mounted near his or her work. Some of these are interesting and some are not, but it was Seattle painter Paul Havas who in articulating his own credo laid out the direction and the danger. "Ever deeper into the visible," he says, "lest the conceptual become formula." The statement is cryptic but seems to mean that, if an artist wants to make something of his own, he had better not try to paint an idea. The visual is difficult, but its abandonment for the realm of the concept is a Faustian sellout. What he gives up for rote formula (which is of course always dressed in elaborate costume and called by another name) is the freshness of his own eyes.

There is no doubt that conception and formula have become boredom in some of the work in this show- I think Michael Spafford's cerebral 13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird is lazy, for example, and Michael Dailey's Blue Bay Night looks like it's been painted 1000 times and hangs in 1000 cool foyers. There are some artists, however, who find that their work gives them freedom. Havas has become our foremost exponent of a "painterly realism" and has incidentally almost single handedly in recent years brought mountains close up into the region's art. (Where are the mountains in the canon? Have they been overlooked?). With his increasingly complex palette Havas has, especially in this show's White Chuck Spine, managed the blurred light and subtle textures of North Cascades contours, the almost underwater look, and their vertiginous attraction, an allure that hums with an ever-so-slight undercurrent of menace. What Havas may be working toward is a painting so far into the visible that it breaks through our accustomed perceptions and unnerves us that like any real love scares us and gives us freedom at the same time.

The Joseph Goldberg selection has a related effect. His large encaustic (wax with color burned in with a torch) Trout Water #2 is an absolutely stunning painting, somehow both monumental and fragile, a geometric abstraction, but one that reports an intimate engagement with the physical world. That world continuously and everywhere gives forth geometry- a basalt column, a circle started from a moth's touch on a pond- but always in this painter's work it is a geometry made rich and imperfect by time.

Years ago another painter, seeing a (small) Goldberg for the first time, remarked to me that he's made it look like an artifact." The best of his paintings live in an element somewhere between rock and language; they make a mysterious peace between fact and message. Physical, geologic and geographic depth is one implication of Goldberg's mastery of his difficult medium; another is temporal depth. The deep spaciousness of time seems to breathe from his color.

At the other end of the building from the Havas and Goldberg paintings, on a wall to itself, is hung an enormous 1992 Richard Gilkey oil, Winter Stone. Gilkey's immediately discernible links are to Morris Graves in his fondness for emblematic figures, and the subject of this superb painting is a single white boulder, grained and fissured like an immense brain in beautifully modulated grays, browns and blacks. Parallel shafts of light or snow of varying intensities slant the ten foot width of the canvas, partially obscuring the stone and building up on its lower part a growing thickness of the snow or of some other unknown opacity. On the lower left march rows of calligraphic script, like burnt smoky ideograms liberated from the rock's own figure. I have no idea why they are there, except that they are perfect. This is one of the most beautiful Gilkeys I've seen, emotionally resonant, even elegiac, and it pushes the limits of symbolic painting without breaking them. It needs to be contemplated in the quiet that it itself produces.

|