|

|

American Knockoff at the Tacoma Art Museum: Bright colors and ugly stereotypes meld in 'American Knockoff'

by Gary Faigan

The Seattle Times, July 28, 2015

American Knockoff at the Tacoma Art Museum: Cartoons and Stereotypes: Two Museum Shows Contrast Roger Shimomura and Chuck Jones

by Brian Miller

The Seattle Weekly, July 7, 2015

Works on Paper exhibition at Hallie Ford Museum of Art:

Oregon exhibit evokes childhood internment for Takei

by Tom Mayhall Rastrell, Stateman Journal

USA Today, November 15, 2014

An American Knockoff: Paintings

August 22 - September 28, 2013

Review in The Seattle Times by Michael Upchurch

Roger Shimomura's 'American Knockoff' is satire at its best

Review in The International Examiner by Susan Kunimatsu

Roger Shimomura Fights Back in 'An American Knockoff'

Review by The Seattle Star:

ROGER SHIMOMURA: NOT MERELY A KNOCK-OFF

Seattle Times

Yellow Terror' art collection: Satire both bright and bitter by Michael Upchurch

Link: here

The Stranger

What Are You, Yellow?

War Breaks Out at the Wing Luke Asian Museum by Jen Graves

From the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 11, 2004

Shimomura explores racism in all its guises -- from the racist's POV

by Regina Hackett

Enough about the victim. Let's hear from the perpetrator.

Roger Shimomura paints racist incidents from the racist's point of view. His cold, flat style -- a blend of American Pop and Japanese ukiyo-e or "floating world" graphics -- gets inside his hot subject and gives it a deadpan edge.

His paintings ring the front room at the Greg Kucera Gallery like small windows to a demented world. Beside each acrylic painting is a terse explanation of its contents, which creates a double-barrel effect: dry facts, fierce visuals.

At 64, Shimomura has a lifetime's worth of experience with racism in all its guises, from the bungling and insensitive to focused hatred. He collects its signs and symbols, including, he says, "Jap hunting licenses, slap-a-Jap cards and movie posters featuring yellow-face actors."

It's the kind of material his parents' generation shunned, but Shimomura agrees with African American painter Kara Walker, who uses racist stereotypes in her work in order to dominate and defuse them: "Change the joke and slip the yoke."

While Walker deals in archetypes, Shimomura gets personal with his own life. Most of these narratives are versions of incidents that happened to him.

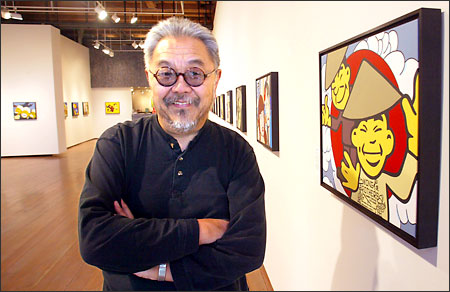

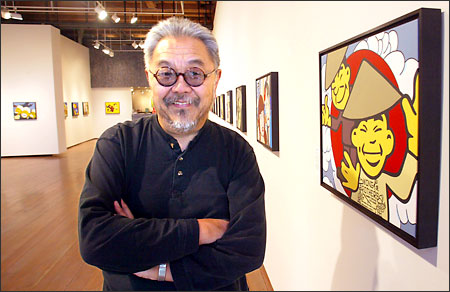

Grant M. Haller / P-I

Painter Roger Shimomura poses with his paintings at the Greg Kucera Gallery. Beside each acrylic painting is a terse explanation of its contents.

Born in Seattle, Shimomura's earliest memories come from Camp Minidoka in Idaho, one of the detention centers in which Japanese Americans were held during World War II thanks to wartime hysteria. Released with his family when he was 5 years old, he returned to Seattle and watched his parents try to rebuild their lives.

In 1961, he received a bachelor's degree in art from the University of Washington, and in 1969 a master's degree in painting from Syracuse University. He has taught at the University of Kansas at Lawrence since 1969, but has family (three adult children) and many friends in Seattle, where he continues to exhibit regularly.

Determined to flourish in a multicultural society, Shimomura likes the metaphor of a tossed-salad better than a melting pot.

Some Japanese Americans became uneasy over comparisons between 9/11 and the Pearl Harbor attack. This shows what the comparison might mean.

Nothing about him has melted, and that includes his memories. They are the basis of his current show, but they do not shape its content.

In high school in 1958, he was dating a white girl from West Seattle against his better judgment, he says, as West Seattle was a well-known hotbed of racism. One night she told him to let her off a block from her home, as her father didn't want her dating "Oriental people" and would kill him if he came to the door. "You think I'm kidding?" she said.

"I remember her getting out of the car and walking away, down the street, past the headlights into the dark," he said.

That's his memory, and it's not what he painted. He painted a cool, Roy Lichtenstein blonde snuggling up to a yellow-skinned demon who licks her with an enormous tongue, a shotgun at his back. He painted himself as "the Jap" the father saw (illustrated below).

A white girl he was dating in 1958 told him her father didn't want her around "Oriental people." The painting portrays the artist as seen by her father.

In the early 1990s, Shimomura had a fresh encounter with the old slur. A woman asked him if he knew what a "JAP" was. As he stared at her, she told him it was a Jewish American Princess. A couple of weeks later, he said, he happened to catch an Oprah show on the theme of "JAPS" or Jewish American Princesses, with no reference to its original meaning.

Shortly thereafter, a Jewish woman conducted a seminar at the University of Kansas, where he teaches, about the word "JAP" and how hurtful it is to Jewish women. His response was not timid or the least bit politically correct: A solo performance piece titled "KIKE," which he said stood for kinky, immature, kimono empress.

Sick of the old slur "jap" getting new life as Jewish American princess, Shimomura responded with "kike" or kinky, immature, kimono empress.

In the painting accompanying this story, a lovely young Jewish woman gazes in the mirror, a crown on her head. Only the first letter of the banner across her chest is visible, and it's a "K."

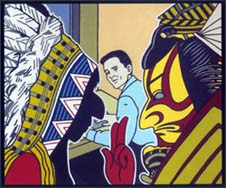

Some experiences that he revisits in paint were bewildering when they occurred. He remembers walking into the administration building at the University of Kansas to sign in his friend, Edgar Heap-of-Birds, who was an artist in residence. An administrator peered out at them and said loudly to the receptionist, "I want you to check the IDs of those two characters out there."

Both men were startled. "We looked at each other," said Shimomura. "What did he say? There's that moment of incredulity, where you can't believe what you just heard."

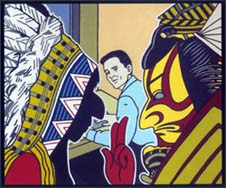

Shimomura and Edgar Heap of Birds were challenged by a young, white administrator where Shimomura teaches. This is what the administrator saw.

In the painting (above), he's an old Japanese warrior and Heap-of-Birds is in full headdress. They talk in the foreground as a young white man peers at them with concern.

The comparison between the tragedy of Sept. 11, 2001, and Pearl Harbor makes a lot of Japanese Americans nervous, he said.

How does he express that concern? With three squinty-eyed, yellow-skinned men painted in turbans flashing impossibly bucked-toothed grins in the foreground as Japanese Zero planes above them head for their targets.

A lot of these paintings are unsettling, but one is unbearable. It features Vincent Chin, the young Chinese American murdered in Detroit in 1982 by white autoworkers who thought he was Japanese and therefore imperiling their jobs. They beat him to death with a baseball bat, and got off with probation and a fine.

Shimomura portrays Chin as a yellow monster in a sea of yellow, soaring in the air like a ball knocked out of the park by a major league slugger. Is this the Vincent Chin his killers saw? There's no pity for him in this painting.

"My emotions aren't in the painting," said Shimomura. "I don't think people care about my emotions. Why would they? Painting allows me to approach this subject in a dispassionate way. It's almost like reporting. This is what is out there. It's dirty work, but I'm compelled to do it."

Photo by Assunta Ng for the Northwest Asian Weekly.

From the Northwest Asian Weekly, March 13, 2004

Reminiscing about racism: Roger Shimomura's art can be uncomfortable but life-changing by Chris S. NishiwakiArtist Roger Shimomura tackles the often uncomfortable topic of racial insensitivity. In his piece “Do You Speak English?,” he recalls the summer 2001 racial profiling incident in which a Seattle police officer verbally harassed a group of Asian American youths.

He's a distinguished professor, yet he insists that he is not trying to teach people.

His art is accessible, yet it conveys complex messages.

His art features bright colors, yet they express very dark topics.

Dichotomy and complexity mark the career of Seattle native Roger Shimomura. They also describe his current art exhibit, “Stereotypes and Admonitions,” a 30-piece collection of acrylic on canvas that chronicles racially insensitive incidents. The exhibit is featured at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle’s Pioneer Square now through March 27.

In “Stereotypes and Admonitions,” Shimomura tackles the often uncomfortable topic of racial insensitivity with full-color accessible pieces. He packs elaborate images and complex stories into a tight format. All the paintings share equal space and billing on the gallery walls. All are a very equitable 20 inches by 24 inches costing $5,000 each.

“If the art is accessible, hopefully people won’t walk away,” Shimomura reasons. “You have to hook them in some kind of way. If I can interest people in any kind of way, it’s a small miracle. If somehow I change their lives, it’s a bigger miracle.”

Some paintings scream of racial stereotypes, featuring exaggerated bucktoothed, slanted-eyed, yellow-skinned characters. Shimomura admits some audience members will be offended and immediately walk away. For those who dig a little deeper, they will find Shimomura’s history and ethics lesson on racial intolerance wrapped into a neat colorful package. Yet Shimomura insists he is not a teacher.

“I don’t feel like I am trying to teach people,” Shimomura said. “I am an artist first. I am not a teacher or an evangelist. There is enough ambiguity in my work. I don’t have to pound you with the subject (of racial intolerance). I let people have their own resolutions.”

In “Do You Speak English?”, Shimomura recalls the summer 2001 racial profiling incident in which a Seattle police officer stopped a group of Asian American youths crossing the street. They were using a marked crosswalk that had no pedestrian signal. The youths were verbally harassed, patted down and asked, “Don’t you know how to cross the street?” “Do you speak English?” “Are you foreigners?”

In Shimomura’s field of muses and inspiration, there are no sacred cows — or Jayhawks, for that matter. Shimomura goes as far as taking on his current employer, the University of Kansas. In “No Thanks,” Shimomura caricatures the school’s mascot, a Jayhawk, by imagining it with buckteeth and slanted eyes. The painting was inspired by the University of Kansas board of regents’ 1942 veto against accepting Japanese Americans to the school.

Shimomura was first moved to portray themes of his ethnic heritage and racial intolerance upon arriving at the University of Kansas in 1969.

“I was part of a very small ethnic minority,” Shimomura recalled.

As his career progressed, he started reaching back to his experiences as a 3-year old interned at Camp Minidoka during World War II. He also borrows from his grandmother’s 56 years of private diary entries.

“My very first memories all came from the camps,” Shimomura said. “The camps burnt those experiences into my mind. Even as a 3-year old.”

Shimomura was born in Seattle in 1939. He was delivered by his grandmother, a certified nurse midwife. A product of Seattle’s public schools, he went to Coleman School, Washington Middle School and Garfield High School before graduating from the University of Washington with a bachelor’s in fine arts in 1961. In between, he spent time in an internment camp and, for a short time, lived in Chicago.

After a two-year military obligation and a few years as a freelance graphic designer, he enrolled in the master’s of fine arts program at the University of Washington in the mid-1960s. He left Seattle in 1967, transferring to Syracuse University, where he earned an MFA in 1969. He joined the University of Kansas fine arts faculty upon graduation. In 1994, he was one of only nine faculty on the entire campus to be promoted to “distinguished professor,” an academic rank higher than the coveted “full professor.” He will retire from the school in May, completing 35 years on the Lawrence, Kan., campus.

“I am looking forward to regaining two-thirds of my life,” Shimomura said.

Upon retirement, he will spend more time in his native Seattle. He will also tour the country promoting another sociopolitical exhibit with Exhibits USA.

Shimomura keeps a home in Seattle and visits at least four times a year, including an extended stretch during the summer. His three grown children live in Seattle, as does his ex-wife, Bea Kiyohara, one of the founders of the Northwest Asian American Theatre.

“Seattle is home,” Shimomura said.

Roger Shimomura’s “Stereotypes and Admonitions” can be viewed at the Greg Kucera Gallery, located at 212 Third Ave. S. in Seattle, through March 27. For more information, call 206-624-0770 or visit www.gregkucera.com.

Chris S. Nishiwaki can be reached at scpnwan@nwlink.com.

From the Kansas City Star from December 19, 2003

Roger Shimomura's Latest Art Exhibit Entertaining and Thought-Provoking

by Kate Hackman

Roger Shimomura's "Stereotypes and Admonitions" is a powerful, poignant exhibition relevant to audiences far broader than just those typically interested in contemporary art.

Perhaps ultimately better suited for a public museum than Jan Weiner's smallish private gallery, it is the sort of widely accessible but content-rich show every citizen would do well to see, consider and discuss.

The exhibition represents the latest manifestation of Shimomura's ongoing exploration of his identity as a third-generation Japanese-American. Shimomura is a distinguished professor of art at the University of Kansas who is soon to retire. He's nationally renowned for paintings and performances that cleverly yet unabashedly confront the prejudices and misperceptions that continue to accompany "difference" in our society.

Central to his work are references to his own life -- from his family's forced relocation from Seattle to an "internment" camp in Idaho during World War II to his experiences as an Asian-American artist based in the Midwest.

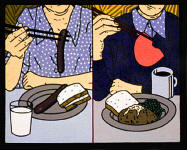

Over several decades, Shimomura has developed a recognizable style. His crisp, flat, lively paintings employ a visual language that juxtaposes and conflates signifiers of East and West -- Superman and Donald Duck, Warhol's Marilyn Monroe, chopsticks, rice bowls and traditionally-costumed kabuki and samurai figures rendered in the style of popular 19th-century Ukiyo-e prints.

Volumes could be written about the sophisticated manner in which Shimomura has exploited, complicated, subverted or reinvented the implications of these cultural icons. This shifting play of signs is one of the great rewards of his work.

In this show, the fantastically image-packed "Yellow Rat Bastard," an installation that includes large-scale portraits of Shimomura and his fellow professor Norman Gee, gives the best sense of Shimomura's ever-expanding lexicon of culturally loaded iconography. Several catalogs on hand at the gallery also provide excellent points of entry for those unfamiliar with Shimomura's previous work.

At the heart of "Stereotypes and Admonitions," however, are the true stories upon which the paintings are based. The 24 paintings on view would deliver quite a punch on their own, but short narratives written by Shimomura and presented on text panels hung alongside the paintings significantly compound the blow.

"Mr. Wong," for example, depicts a dark-skinned, bucktoothed cartoon caricature of an Asian male surrounded by Veronicas and Bettys from the Archie comics. The painting itself perfectly encapsulates the contrast between idealized -- though equally stereotypical -- white suburban cheerleaders and the anti-idealized, powerless "foreigner" who seems about to be devoured by the girls' gleaming smiles.

The text explains that Mr. Wong appeared as an Internet cartoon in 1999 and has refused to go away despite extensive protests from the Asian community.

Many of these stories are based on the artist's experiences; others make note of racism readily observable by anyone. These include the opening of a store in New York called Yellow Rat Bastard or the Abercrombie & Fitch T-shirts featuring "smiling men with slanted eyes wearing conical hats" and bearing slogans including "Buddha Bash" and "Wok-n-Bowl." Some testify to assumptions based on ignorance, while others document nearly unfathomable examples of racially based hatred and violence.

Confidently and dexterously translating the stories into images that communicate with clarity and a sense of immediacy, Shimomura's paintings are effective in part because of their specificity and directness. They relate real, lived experiences in a manner that is not afraid of crossing taboos and producing discomfort. Considered as an entirety, the images yield a portrait of a range of types and realms of discrimination, ultimately transcending their specificity to create a larger portrait of the dynamics and frameworks of racism in general.

The result seems to be exactly what Shimomura intends: to remind us that new stories of racial discrimination are being written every day and to propel us toward a heightened consciousness of our own perceptions, beliefs and actions. Viewers cannot help but feel implicated in these narratives, either as perpetrators or victims, and thus are forced to confront the responsibilities that accompany that point of identification.

It's not a new subject, but Shimomura continues to address it with finesse, freshness and intelligence.

For those who miss this excellent show, a catalog of the work, featuring an essay by Lucy R. Lippard, will be released in the spring. Recently Shimomura was named one of 10 recipients from a field of 60 nominees for a 2003 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award recognizing excellence in painting and sculpture. He will give a free lecture about his work at 7 p.m. Jan. 9 in Atkins Auditorium at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 4525 Oak St, Kansas City

Radio review of Roger Shimomura's "An American Diary" exhibition at Bellevue Art Museum Broadcast December 2001, KUOW Seattle

Roger Shimomura by Gary Faigin

Artist Roger Shimomura is no stranger to Seattle audiences. A Seattle native who has lived in Lawrence, Kansas for many years, Shimomura has been showing at the Greg Kucera Gallery in Pioneer Square since 1985. Also familiar to many local viewers are Shimomura’s large murals in the Westlake Station of the downtown bus tunnel.

Much of Roger Shimomura’s work reflects his experience as an American of Japanese descent, experiences that include his family’s relocation to an internment camp during World War II. Now the Bellevue Art Museum is hosting An American Diary, a show featuring 30 paintings based on his grandmother’s accounts of that period. The works are the centerpiece of an exhibition making its last stop in Seattle after an extensive national tour. The show has been widely heralded as both an educational and an artistic event. For the artistic perspective, here is our critic, Gary Faigin.

Almost everything about the An American Diary show at the Bellevue Art Museum is modest. The paintings themselves, though numerous, are small and extremely restrained, in mood, style, and color. The excerpts from grandmother Toku Shimomura’s diaries, engraved on little plaques below each painting, are mild in tone and terse in language. Though the events that Toku describes, the temporary ethnic cleansing of the US West Coast in the 1940s, was a major trauma for thousands of people like herself, her sense of anger and despair is mostly to be read between the lines. The paintings address this historical wrong quietly, and ironically.

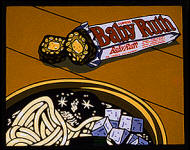

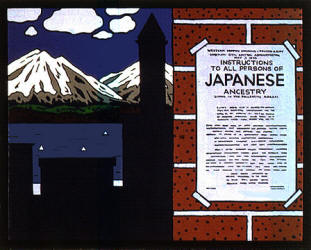

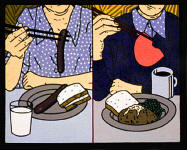

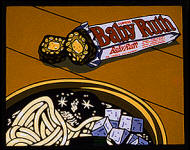

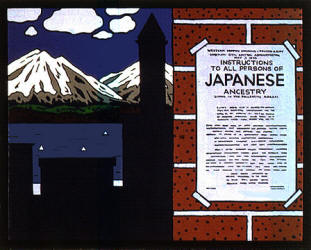

A sense of emotions boiling under a decorous surface, and the artistic employment of irony, have long been trademarks of the work of grandson Roger Shimomura. His painting in general combines the flat, decorative boldness of Japanese prints with the brand-name slickness of American pop art. Baby Ruth candy bars exist side by side with chopsticks, tofu, and Udon noodles, GI Joe rubs elbows with silk-robed samurai. Superman makes a more than occasional appearance, and his nemesis often has purposely sinister Oriental features. Repeated elements serve as a symbolic language – brick walls stand in for America, for example, translucent screens for Japan.

The current show depends heavily on familiar comic book precedents for the narrative look of the panels. The beautifully drawn characters and settings are simple, cleanly outlined and filled in with wan, flat color. Occasional comic celebrities make an appearance, alter egos for an aroused Uncle Sam. A squinting Dick Tracy, for example, fills the foreground of one image, peering through a lens at the fingerprints of Grandmother Shimomura, whose featureless silhouette is seen waiting passively in the doorway beyond. “I finally decided to register my fingerprints today after putting this off for a long time” writes Toku laconically. In another panel heavy with irony, Superman himself is seen landing just outside the Shimomura house, as Grandmother writes of her appreciation of “American large-heartedness” in the days just after the beginning of the war. We know better - Superman is not in fact coming to her rescue - he is instead about to save us from her.

The sheer artistic skill of Roger Shimomura both elevates and lightens the effect of the work. The very first painting in the show is a ravishing image of Grandmother half hidden by a shoji screen, with the distinctive shape of the art deco radio in the foreground echoed in her face and the patterns on her dress. One can easily forget the horror of the moment depicted – the announcement of the attack on Pearl Harbor – in admiring the sophistication of the color and design. Other pictures are more successful in conveying the intended message, particularly those which use Shimomura’s style to highlight the bleakness of the camp environment, or come in close on Grandmother’s face and hands as she swallows a sleeping pill or measures her blood pressure.

An even more instructive contrast in tone is provided by comparing the An American Diary show with several larger Shimomura paintings in an adjoining galley. One picture in particular, a spectacular tour de force entitled A Sansei Story, shows just how much Shimomura is holding back to keep company with his soft-spoken grandmother. This giant painting is an extravaganza of bombastic imagery and glorious excess, a collage of sex, violence, artistic borrowings, childhood memories, and self-portraits, all held together in a brilliant billboard-inspired design.

It will be for each visitor to decide if Roger Shimomura’s quiet treatment of the charged theme of Japanese internment lets them off the hook or draws them further in. Topicality in art, particularly when dealing with sweeping historical events, is never an easy proposition.

|